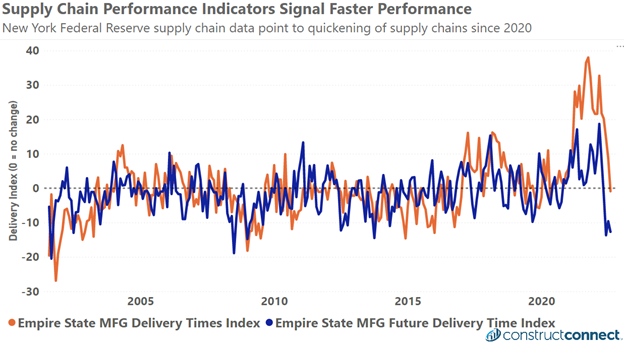

The August data released by the New York Federal Reserve for their Empire State Manufacturers Delivery Time Index pointed to a slight contractionary reading of -0.9. This marks the first time since COVID-19 that the Fed’s supply chain survey has pointed to faster supply chain performance.

This quickening performance reading could have resulted from either or both of two general causes: 1.) greater supply chain capacity and throughput and 2.) weakening demand on supply chains, allowing remaining orders to move more quickly through a less congested system.

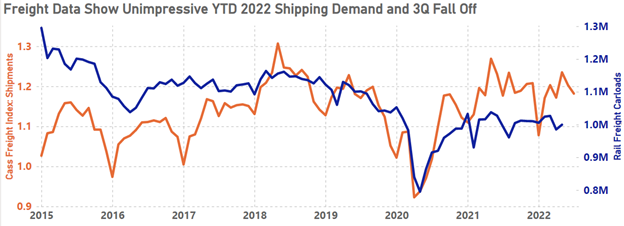

The idea that supply-side improvements in transportation networks are generally responsible for quicker supply chain performance is difficult to accept given the system’s continuing labor shortages and China’s austere COVID-19 policies which continue to interrupt international supply chain performance. U.S. transportation data monitoring tons of cargo moved by air, sea, and land throughout 2022 has shown little discernable net change with rail freight carloads down and trucking freight up only very slightly. The Cass Freight Index: Shipments, a measure of the number of intracontinental freight shipments across North America, has shown no discernable long-run change. The index continues to oscillate around a reading of 1.18, the same reading it reported in April of 2021.

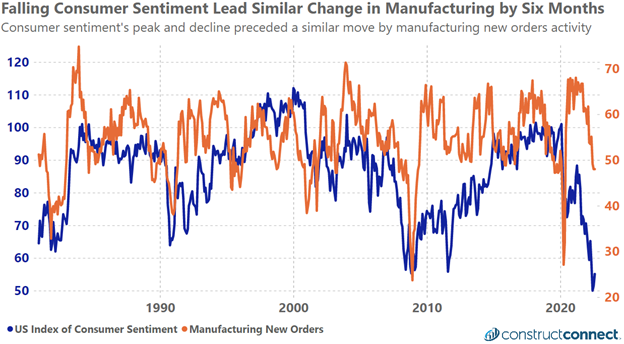

Conversely, several data series suggest that a weakening consumer is the root cause for declining demand in manufacturing and ultimately transportation services. High levels of inflation over the last two years have significantly eroded the purchasing power of wages, thus souring consumers’ outlook and spending habits.

The U.S. Index of Consumer Sentiment peaked in April of 2021 before entering a prolonged slide that would culminate in a June 2022 nadir and historic low reading. The knock-on effects from this have been made apparent in the manufacturing new orders activity data. New orders activity readings began declining in October 2021—six months after a similar turn in consumer sentiment—indicating slowing expansion. It would not be until June 2022 that new orders activity contracted, followed by an accelerating contraction reading the following month.

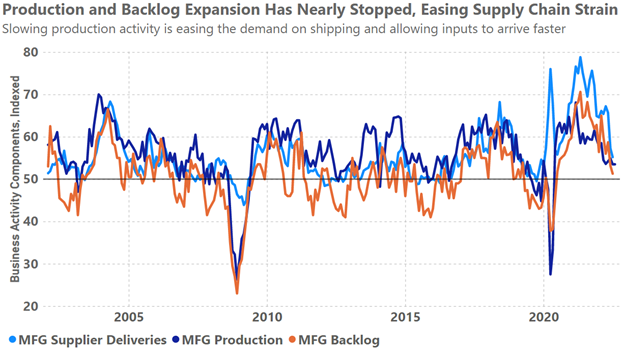

The shifting trend in new orders activity has been keenly felt on the factory floor with sequential months of production activity readings pointing to slowing expansion. The latest data pointed to the slowest expansion in production and backlog activity since COVID-19’s initial disruption in early 2020. Slowing production activity has allowed manufacturers to focus on reducing backlogs, causing backlog activity to slow even more quickly thus far in the second half of 2022.

The behavior of consumers has long been known to be a bellwether for the direction of much of the rest of the economy. For this reason, any future signals of improving supply chain conditions need to be considered relative to the condition of the consumer and ultimately their demand for new orders.

Without this consideration, it will be impossible to know whether supply chains are improving in the face of a strong economy, or if their problems have simply become trivial in the face of a worsening economy. Knowing the difference will be essential for those tasked with making forward-looking business decisions and managing future inventories.